Sapiens: A brief history of humankind

A book which answers questions about who we are, how we got here, and where we’re going.

The book covers three revolutions: the cognitive revolution (70,000 years ago), the agricultural revolution (12,000 years ago), and the scientific revolution (500 years ago).

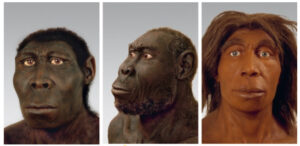

The first interesting part of the book (IN MY OPINION) discusses the evolution of sapiens into different species. You’ve got your classic Neanderthals (yes, like the ones from Night at the Museum) but you’ve also got homo rudolfensis, homo denisova, homo soloensis, and homo erectus (there’s more btw).

Neanderthals (meaning man from the Neander Valley) were from Europe and Western Asia. They were hench af as they had adapted to the cold climates of Ice Age western Eurasia. In east Asia, you’ve got homo erectus (no, not that kind, it means ‘upright man’). This species was hard af and was the most durable species surviving on earth for close to 2 million years. This record is unlikely to be broken even by our own species. I mean it’s doubtful that homo sapiens will still be around 1000 years from now, let alone 2 million!

Left to right: Homo Rudolfensis (East Africa), Homo Erectus (East Asia), and Homo Neanderthalensis (Europe and Western Asia).

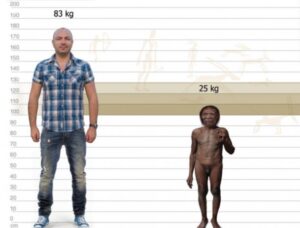

The chapter goes on to talk about another species of human: Homo Floresiensis, located on the island of Flores, Indonesia. This species of human underwent a process of dwarfing. When the first humans got to the island the sea levels were exceptionally low, when the sea levels rose again, some people were trapped on the island. The island was poor in resources and naturally, the big people (who needed lots of food to survive), died. The smaller people survived much better and over the generations, the Flores people became dwarves.

Homo floresiensis reached a maximum height of only ONE METRE and weighed no more than 30 kg!

On the right is a little Indonesian hobbit next to a modern-day homo sapien.

It’s a common myth that we evolved in a straight line of descent (google ‘evolution’, you’ll see what I mean). That mistakenly implies that one species roamed the earth after the other. In reality, there were several species of humans floating about in one period of time. But what’s even more strange is that we’re the only species left.

The reason for this is our fat brains and our love for gossiping. No really, the cognitive revolution is based on gossip theory, where studies have shown the development of language vastly improved homo sapiens’ ability to share information with other homo sapiens. Information such as hunting tips, whereabouts of food sources, and warnings of dangerous threats – all resulted in tighter, more sophisticated types of cooperation between bands of sapiens. Yet the truly unique feature was the ability for sapiens to share information about things that did not exist at all. This ability to speak about fiction is the most unique feature of sapiens as a species.

When we look at chimpanzees, there are clear limits to the size of their groups. As the numbers in the group increase, the social order between the chimps destabilises and the groups split off into new ones. So how did sapiens manage to cooperate in large numbers? The secret was most likely fiction.

Any large-scale cooperation, whether a modern state or a small ancient tribe – is rooted in common myths that exist only in people’s collective imagination. Two Catholics who have never met might hold hands and pray together because they both believe that God allowed himself to be crucified to redeem our sins. Two Kurds who have never met might defend one another because they both believe in the existence of the nation of Kurdistan. Two human rights lawyers who have never met might band together and defend someone because they believe in justice and equality. Yet all of these things are fiction, they are imagined realities which generate commonality. It is these imagined commonalities (myths, legends, religions, etc.,) that enabled sapiens to establish social order and hierarchies.

Next up, the agricultural revolution.

This part of the book talks about societies crossing a critical threshold, where the amount of people and property necessitated the storage and processing of large amounts of mathematical data. The first to overcome the problem was the ancient Sumerians, who lived in southern Mesopotamia. As the population grew, they invented a system of storing numbers outside of their brains that in essence, released their social order from the limitations of the human brain, paving the way for cities, kingdoms, and empires.

Writing is a method of storing information through material signs. The Sumerian system did this by combining two types of signs, which were pressed into clay tablets. One type of sign represented numbers 1, 10, 60, 600, 3600, and 36,000. Fun fact alert – the Sumerians used a combination of base-6 and base-10 numeral systems, which have since evolved into the systems we know and use today, such as dividing days into twenty-four hours and circles into 360 degrees.

Between 3000 BC and 2500 BC more and more signs were added to the Sumerian system, gradually transforming it into a full script that we today call cuneiform. At roughly the same time, the Egyptians developed another full script known as hieroglyphics. What set apart the Sumerians, was the techniques they used to archive, catalogue and retrieve written records.

The creation of modern mathematics.

As the centuries passed, a critical step was made just before the ninth century AD. A new script was invented which enabled people to store and process mathematical data with unprecedented efficiency. This script consisted of ten signs, representing numbers from 1-9. It is known as the Arab numerals, even though the Hindus invented it (but because the Arabs invaded India, stole the system, and spread it through the Middle East and to Europe, they get the credit for it). Once the addition, subtraction and multiplication signs were added to the numerals, the basis of modern mathematical systems came into being.

The chapter continues looking at the development of societies and discusses how hierarchical structures are formed through the classification of people using narratives of purity and pollution. An interesting point is made about a vicious circle which perpetuates racial hierarchy in modern America. From the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, European conquerors imported millions of African slaves to work the mines and plantations of America for three key reasons.

- Africa was closer, so it was cheaper to important slaves from Senegal rather than Vietnam.

- There was already a developed slave trade in Africa (exporting slaves to the Middle East), whereas in Europe slavery was rare.

- American plantations such as Virginia, Haiti and Brazil were plagued by Malaria and yellow fever, which had originated in Africa. Africans had acquired genetic immunity to these diseases over the years, whereas Europeans were defenceless and died in masses. Ironically, it was the African genetic superiority (immunity) that resulted in social inferiority.

FeMENism?

An interesting point is also made about the historical superiority of men over women. Regardless of the different societies, races, religions, and cultures in all of history, the one thing they all have in common is the hierarchy of gender. Some of the earliest Chinese texts talks about the misfortune of giving birth to a girl, over a boy. It talks about how in many societies women were simply the property of men, most often, their fathers, husbands or brothers. Rape, in many, legal systems falls under property violation, in other words, the victim is not the woman who has been raped, but the male who owns her.

The legal remedy was, therefore, to pay the ‘bride’s price’ to the woman’s father/brother/owner, upon which she became the rapist’s property. No seriously, this was a real thing. The bible states “If a man meets a virgin who is not betrothed (engaged), and seizes her and lies with her, and they are found, then the man who lay with her shall give to the father of the young woman fifty shekels of silver and she shall be his wife” – Deuteronomy 22:28-9).

Raping a woman who did not belong to any man was not considered a crime at all. Just as picking up a lost coin on a busy street is not considered theft. If a husband raped his own wife, he had committed no crime. The idea that a husband could rape his own wife, was literally an oxymoron back then, it was akin to a man stealing his own wallet. As of 2006, there were still fifty-three countries where a husband could not be prosecuted for the rape of his wife. Even in Germany, rape laws were amended only in 1997 to create a legal category of marital rape.

In democratic Athens of the fifth century BC, an individual possessing a womb had no independent legal status and was forbidden to participate in popular assemblies, be a judge, be educated, and participate in political, business or philosophical discourse. None of Athens’ political leaders, none of its great philosophers, orators, artists, or merchants had a womb. Did having a womb make these people unfit, biologically to do these things? If they can do these things now, what has changed?

In a similar vein, most modern Greeks see heterosexual relationships as natural and homosexual relationships as unnatural. They don’t see this as a cultural bias but as a biological reality. A significant number of cultures have seen homosexual relations as entirely legitimate and socially constructive, Ancient Greece being the most notable example. So how are we able to distinguish what is biologically determined from what people merely try to justify through biological myths? The answer is that “Biology enables, culture forbids”.

Biology enables women to have children, culture obliges women to do so. Biology enables men to enjoy sex with each other, but culture forbids them to realise this possibility. The argument that homosexual intercourse is ‘unnatural’ is scientifically incorrect. From a biological perspective, nothing is unnatural. Whatever is possible is by definition also natural. A truly unnatural behaviour, one that goes against the laws of nature, simply cannot exist. You don’t hear of cultures banning men from photosynthesising, or women running faster than the speed of light, or snails flying. Chimpanzees, for example, use sex to cement political alliances, establish intimacy, and defuse tensions – is that unnatural?

In summary, most of the laws, norms, rights and obligations that define manhood and womanhood reflect human imagination more than biological reality.

The next part of the book covers globalisation and offers an interesting example of globalisation – ethnic cuisine. In an Italian restaurant, we expect to find spaghetti in tomato sauce, in Polish and Irish restaurants lots of potatoes, in Argentinian restaurants we have the choice of lots of different steaks, in Indian restaurants most of the curries contain hot chillies and the highlight of any swiss cafe is a hot chocolate with whipped cream. None of these foods are native to those nations. Tomatoes, chilli peppers and cocoa are all Mexican in origin. They reached Europe and Asia only after the Spaniards conquered Mexico. Potatoes only reached Poland and Ireland no more than 400 years ago (originally from southern Peru) and the only steak you could obtain in Argentina in 1492 was from a llama.

The invention of money.

Money throughout history has taken many shapes and forms. In essence, it is anything that people are willing to use to represent value. For around 4000 years, shells were used as money all across Africa, Southern and Eastern Asia and Oceania. Believe it or not, taxes could still be paid in cowry shells in British Uganda in the early twentieth century! If only HMRC would consider this as a valid payment method … of course they wouldn’t, they’re shellfish.

The invention of money.

Money throughout history has taken many shapes and forms. Money is anything that people are willing to use in order to systematically represent the value of other things for the purpose of exchanging goods and services. For around 4000 years, shells were used as money all across Africa, Southern and Eastern Asia and Oceania. Believe it or not, taxes could still be paid in cowry shells in British Uganda in the early twentieth century! If only HMRC would consider this as a valid payment method … of course they wouldn’t, they’re shellfish.

The real breakthrough with money came in ancient Mesopotamia with the creation of the silver shekel. The silver shekel was not a coin, but rather 8.33 grams of silver and it was the set weights of precious metals that eventually gave birth to coins. The first coins in history were struck around 640 BC by King Alyattes of Lydia, in western Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). These coins had a standardised weight of gold or silver and were imprinted with an identification mark. The mark affirmed two things. First, it indicated how much precious metal the coin contained. Second, it identified the authority that issued the coin and guaranteed its contents. Almost all coins in use today are descendants of the Lydian coins.

Fun fact – In the first century AD, Roman coins were in use all the way in India! The Indians had such strong confidence in the denarius (name of the coin) that they based their own coins on it (even copying the portrait of the Emporer!). The name ‘denarius’ became the generic name for ‘coins’ which was later Arabicised into the ‘dinar’. The dinar is still the official name of the currency in Jordan, Iraq, Serbia, Macedonia, Tunisia, and several other countries.

While on this topic, the book makes an interesting point about the formation of cultures we know and see today. Modern Jews, for example, owe far more to the empires under which they lived during the past two millennia than to the traditions of the ancient kingdom of Judea. If King David were to show up in an ultra-Orthodox synagogue in present-day Jerusalem, he would be utterly bewildered to find people dressed in Eastern European clothes, speaking in a German dialect (Yiddish) and having endless arguments about the meaning of a Babylonian text (the Talmud). There were neither synagogues, volumes of Talmud, nor even Torah scrolls in ancient Judaea.

Another interesting fact – the Taj Mahal, a famous landmark native to India was actually built by Muslim conquerers. Commissioned in 1631, the fifth Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal to house the tomb of his beloved wife, Mumtaz Mahal.

Christianity V Catholicism

On the topic of religion, the book covers the classic Catholicism V Christianity division. In summary, the only god that the Romans refused to tolerate was the monotheistic god of the Christians. The Roman Empire didn’t require the Christians to abandon their faith but it did expect them to pay respect to the empire’s protector gods and the divinity of the emperor. However, the Christians responded with a big fat no which was seen as political disloyalty to the Romans. The Romans reacted with classic persecution to what they understood to be a politically subversive faction.

In the 300 years from the crucifixion of Christ to the conversion of Emperor Constantine, Roman emperors initiated four general persecutions of Christians. And if you combined all the victims of all these persecutions, it turns out that in these three centuries, the polytheistic Romans killed no more than a few thousand Christians. In contrast, over the next 1,500 years, Christians slaughtered Christians by the millions to defend slightly different interpretations of the religion of love and compassion.

These religious disputes turned so violent that during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Catholics and Protestants killed each other by the hundreds of thousands. On 23 August 1572, French Catholics (who stressed the importance of good deeds, lol) attacked communities of French Protestants who highlighted God’s love for humankind. In the attack, AKA the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, between 5,000 and 10,000 Protestants were slaughtered in less than twenty-four hours.

When the pope in Rome heard the news from France, he was so overcome by joy that he organised festive prayers to celebrate the occasion and commissioned Giorgio Vasari to decorate one of the Vatican’s rooms with a painting of the massacre (sicko?).

In summary, more Christians were killed by fellow Christians in those twenty-four hours than by the polytheistic Roman Empire throughout its entire existence.

Painting by François Dubois, a Huguenot painter who fled France after the massacre. Although it is not known whether Dubois witnessed the event, he depicts Admiral Coligny’s body hanging out of a window at the rear to the right. To the left rear, Catherine de’ Medici is shown emerging from the Louvre Palace to inspect a heap of bodies.

TRENDY NEW RELIGIONS.

Before the prevalent religions of today, there were thousands of gods and goddesses to pray to. From tribes performing sacrifices and fire dances to appease the god responsible for bringing rain to Greek and Norse mythology – where there were gods for just about anything. Seriously, look up ‘Dionysus’.

Anyways, polytheism (belief in many gods) became uncool and in rolled a trendy new type of religion = monotheism (belief in one god).

All the polytheistic religions booted out their gods through the front door, only to take them back in through the side window disguised as ‘saints’. For example, the chief goddess of Celtic Ireland prior to the coming of Christianity was Brigid. When Ireland was Christianised, Brigid too was baptised. She became St Brigit, who to this day is the most revered saint in Catholic Ireland…

On the topic of hypocrisy, the belief in heaven (place of good) and hell (place of evil) was also manufactured over time. There is no trace of this belief in the Old Testament, which also never claims that the souls of people continue to live after the death of the body.

The average Christian believes in the monotheist God, but also in the dualist Devil and in polytheist saints. Scholars of religion have a name for this simultaneous avowal of different and even contradictory ideas and the combination of rituals and practices taken from different sources. It’s called syncretism.

But that’s not to say that science can answer all the questions that religion can’t. After centuries of extensive scientific research, biologists admit that they still don’t have any good explanation for how brains produce consciousness. Physicists admit that they don’t know what caused the Big Bang, or how to reconcile quantum mechanics with the theory of general relativity. So put the Bible (or Bunsen burner) down, and chill out, yeah?

MATHS + DEATH CLERGYMEN= PROFIT

I don’t really know how to segway into this next part, but just know that when I read it and gasped a little at the end.

In 1744, two Scottish clergymen, Alexander Webster and Robert Wallace, decided to set up a scheme that would provide pensions for the widows and orphans of dead clergymen. They proposed that each of their church’s ministers would pay a small portion of his income into the fund, which would invest the money. If a minister died, his widow would receive dividends on the fund’s profits. This would allow her to live comfortably for the rest of her life. But to determine how much the ministers had to pay in so that the fund would have enough money to live up to its obligations, Webster and Wallace had to be able to predict how many ministers would die each year, how many widows and orphans they would leave behind, and by how many years the widows would outlive their husbands.

So they contacted a professor of mathematics from the University of Edinburgh, Colin Maclaurin. The three of them collected data on the ages at which people died and used these to calculate how many ministers were likely to pass away in any given year.

For example, a twenty-year-old person has a 1:100 chance of dying in a given year, but a fifty-year-old person has a 1:39 chance.

Their work was founded on several recent breakthroughs in the fields of statistics and probability. One of these was Jacob Bernoulli’s Law of Large Numbers. Bernoulli had codified the principle that while it might be difficult to predict with certainty a single event, such as the death of a particular person, it was possible to predict with great accuracy the average outcome of many similar events.

Processing these numbers, Webster and Wallace concluded that, on average, there would be 930 living Scottish Presbyterian ministers at any given moment, and an average of twenty-seven ministers would die each year, eighteen of whom would be survived by widows. Five of those who did not leave widows would leave orphaned children, and two of those survived by widows would also be outlived by children from previous marriages who had not yet reached the age of sixteen. They further computed how much time was likely to go by before the widows’ death or remarriage (in both these eventualities, payment of the pension would cease). These figures enabled Webster and Wallace to determine how much money the ministers who joined their fund had to pay in order to provide for their loved ones. By contributing £2 12s. 2d. a year, a minister could guarantee that his widowed wife would receive at least £10 a year – a hefty sum in those days.

According to their calculations, by the year 1765 the Fund for a Provision for the Widows and Children of the Ministers of the Church of Scotland would have capital totalling £58,348. Their calculations proved amazingly accurate. When that year arrived, the fund’s capital stood at £58,347 – just £1 less than the prediction!

Today, Webster and Wallace’s fund, known simply as Scottish Widows, is one of the largest pension and insurance companies in the world. With assets worth £100 billion, it insures not only Scottish widows but anyone willing to buy its policies (obvs).

THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

This part of the book focuses on the scientific revolution. I have selected the parts that I found interesting.

The invention of gunpowder.

The most important military invention in the history of China was gunpowder. Yet to the best of our knowledge, gunpowder was invented accidentally, by Daoist alchemists searching for the elixir of life. Gunpowder’s subsequent career is even more telling. One might have thought that the Daoist alchemists would have made China master of the world. In fact, the Chinese used the new compound mainly for firecrackers. Even as the Song Empire collapsed in the face of a Mongol invasion, no emperor set up a medieval Manhattan Project to save the empire by inventing a doomsday weapon. Only in the fifteenth century – about 600 years after the invention of gunpowder – did cannons become a decisive factor on Afro-Asian battlefields. Why did it take so long for the deadly potential of this substance to be put to military use? Because it appeared at a time when neither kings, scholars, nor merchants thought that new military technology could save them or make them rich.

LIGHTENING = ELECTRICITY?!

In the middle of the eighteenth century, in one of the most celebrated experiments in scientific history, Benjamin Franklin flew a kite during a lightning storm to test the hypothesis that lightning is simply an electric current. Franklins empirical observations, coupled with his knowledge about the qualities of electrical energy, enabled him to invent the lightning rod and disarm the gods.

DISTANCE OF THE SUN = GENOCIDE?

The book talks about a time in history when humans wanted to measure how far away the sun was from the Earth. A reliable means of making the measurement was finally proposed in the middle of the eighteenth century. Every few years, the planet Venus passes directly between the sun and the earth. The duration of the transit differs when seen from distant points on the earth’s surface because of the tiny difference in the angle at which the observer sees it. If several observations of the same transit were made from different continents, simple trigonometry was all it would take to calculate our exact distance from the sun.

Astronomers predicted that the next Venus transits would occur in 1761 and 1769. So expeditions were sent from Europe to the four corners of the world to observe the transits from as many distant points as possible. In 1761 scientists observed the transit from Siberia, North America, Madagascar and South Africa. As the 1769 transit approached, the European scientific community mounted a supreme effort, and scientists were dispatched as far as northern Canada and California (which was then a wilderness). The Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge concluded that this was not enough. To obtain the most accurate results it was imperative to send an astronomer all the way to the south-western Pacific Ocean.

The Royal Society resolved to send an eminent astronomer, Charles Green, to Tahiti, and spared neither effort nor money. But, since it was funding such an expensive expedition, it hardly made sense to use it to make just a single astronomical observation. Green was therefore accompanied by a team of eight other scientists from several disciplines, headed by botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander. The team also included artists assigned to produce drawings of the new lands, plants, animals and peoples that the scientists would no doubt encounter. Equipped with the most advanced scientific instruments that Banks and the Royal Society could buy, the expedition was placed under the command of Captain James Cook, an experienced seaman as well as an accomplished geographer and ethnographer.

The expedition left England in 1768, observed the Venus transit from Tahiti in 1769, observed several Pacific islands, visited Australia and New Zealand, and returned to England in 1771. It brought back enormous quantities of astronomical, geographical, meteorological, botanical, zoological and anthropological data. Its findings made major contributions to several disciplines, sparked the imagination of Europeans with astonishing tales of the South Pacific, and inspired future generations of naturalists and astronomers.

The darker side to this, obviously, is that the Cook expedition laid the foundation for the British occupation of the south-western Pacific Ocean; for the conquest of Australia, Tasmania and New Zealand; for the settlement of millions of Europeans in the new colonies; and the eradication of their native cultures and most of their native populations.

In the century following the Cook expedition, the most fertile lands of Australia and New Zealand were taken from their previous inhabitants by European settlers. The native population dropped by up to 90 per cent and the survivors were subjected to a harsh regime of racial oppression. For the Aborigines of Australia and the Maoris of New Zealand, the Cook expedition was the beginning of a catastrophe from which they have never recovered.

An even worse fate befell the natives of Tasmania. Having survived for 10,000 years in splendid isolation, they were completely wiped out, to the last man, woman and child, within a century of Cook’s arrival.

The invention of the rail

In 1825, a British engineer connected a steam engine to a train of mine wagons full of coal. The engine drew the wagons along an iron rail some twenty kilometres long from the mine to the nearest harbour. This was the first steam-powered locomotive in history. Clearly, if steam could be used to transport coal, why not other goods? And why not even people? On 15 September 1830, the first commercial railway line was opened, connecting Liverpool with Manchester.

The world’s first commercial railroad opened for business in 1830, in Britain. By 1850, Western nations were crisscrossed by almost 40,000 kilometres of railroads – but in the whole of Asia, Africa and Latin America there were only 4,000 kilometres of tracks!

Random interesting fact.

In 1831, the Royal Navy sent the ship HMS Beagle to map the coasts of South America, the Falklands Islands and the Galapagos Islands. The navy needed this knowledge in order to be better prepared in the event of war. The ship’s captain, who was an amateur scientist, decided to add a geologist to the expedition to study geological formations they might encounter on the way. After several professional geologists refused his invitation, the captain offered the job to a twenty-two-year-old Cambridge graduate, Charles Darwin!

NEW YORK NEW YORK!

The most famous Dutch joint-stock company, the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC for short, was chartered in 1602. While VOC operated in the Indian Ocean, the Dutch West Indies Company, or WIC, plied the Atlantic. To control trade on the important Hudson River, WIC built a settlement called New Amsterdam on an island at the river’s mouth. The colony was threatened by Indians and repeatedly attacked by the British, who eventually captured it in 1664. The British changed its name to New York. The remains of the wall built by WIC to defend its colony against Indians and British are today paved over by the world’s most famous street – Wall Street.

WHAT’S WRONG? WE’RE TAKING HONG KONG!

The book brilliantly illustrates how governments did the bidding of big money using the First Opium War, fought between Britain and China (1840–42) as a key example. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the British East India Company and British businesspeople made fortunes by exporting drugs, particularly opium, to China. Subsequently, millions of Chinese became addicts, debilitating the country both economically and socially. In the late 1830s, the Chinese government issued a ban on drug trafficking, but British drug merchants simply ignored the law. Chinese authorities began to confiscate and destroy drug cargos. The drug cartels had close connections in Westminster and Downing Street – many MPs and Cabinet ministers in fact held stock in the drug companies – so they pressured the government to take action.

In 1840 Britain duly declared war on China in the name of ‘free trade’. It was an easy win. The overconfident Chinese were no match for Britain’s new wonder weapons – steamboats, heavy artillery, rockets and rapid-fire rifles. Under the subsequent peace treaty, China agreed not to constrain the activities of British drug merchants and to compensate them for damages inflicted by the Chinese police. Furthermore, the British demanded and received control of Hong Kong, which they proceeded to use as a secure base for drug trafficking (Hong Kong remained in British hands until 1997). In the late nineteenth century, about 40 million Chinese, a tenth of the country’s population, were opium addicts. Nice one, Britain.

Energy ConSUNption

The book questions why so many people are afraid that we are running out of energy. It asks why there are warnings of disaster if we exhaust all available fossil fuels. It argues that the world clearly does not lack energy. All we lack is the knowledge necessary to harness and convert it to our needs. The amount of energy stored in all the fossil fuels on earth is negligible compared to the amount that the sun dispenses every day, free of charge.

Only a tiny proportion of the sun’s energy reaches us, yet it amounts to 3,766,800 exajoules of energy each year (a joule is a unit of energy in the metric system, about the amount you expend to lift a small apple one yard straight up; an exajoule is a billion billion joules – that is a LOT of apples). All the world’s plants capture only about 3,000 of those solar exajoules through the process of photosynthesis. All human activities and industries put together consume about 500 exajoules annually, equivalent to the amount of energy Earth receives from the sun in just ninety minutes and that’s only solar energy. In addition, we are surrounded by other enormous sources of energy, such as nuclear energy and gravitational energy, the latter most evident in the power of the ocean tides caused by the moon’s pull on the earth.

FANCY ALUMINIUM

Chemists discovered aluminium only in the 1820s, but separating the metal from its ore was extremely difficult and costly. Believe it or not, for decades, aluminium was much more expensive than gold. In the 1860s, Emperor Napoleon III of France ordered aluminium cutlery to be laid out for his most distinguished guests. Less important visitors had to make do with the gold knives and forks!!

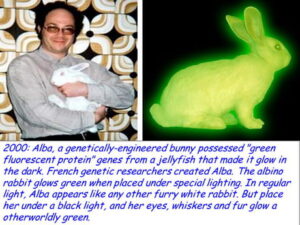

ALBA GREEN RABBIT.

Eduardo Kac, a Brazilian bio-artist, decided in 2000 to create a new work of art: a fluorescent green rabbit. Kac contacted a French laboratory and offered it a fee to engineer a radiant bunny according to his specifications. The French scientists took a run-of-the-mill white rabbit embryo, implanted in its DNA a gene taken from a green fluorescent jellyfish, and voilà! One green fluorescent rabbit for le monsieur. Kac named the rabbit Alba.